NOBODY KNOWS, NOBODY KNEW

Lateral view

Infinite Rewrite XXX, 2016 Analogue photogram on chromogenic paper, aluminum mount on stacked acrylic base 10.43 x 8.38 x 1.41 in. / 26.5 x 21.3 x 3.6 cm

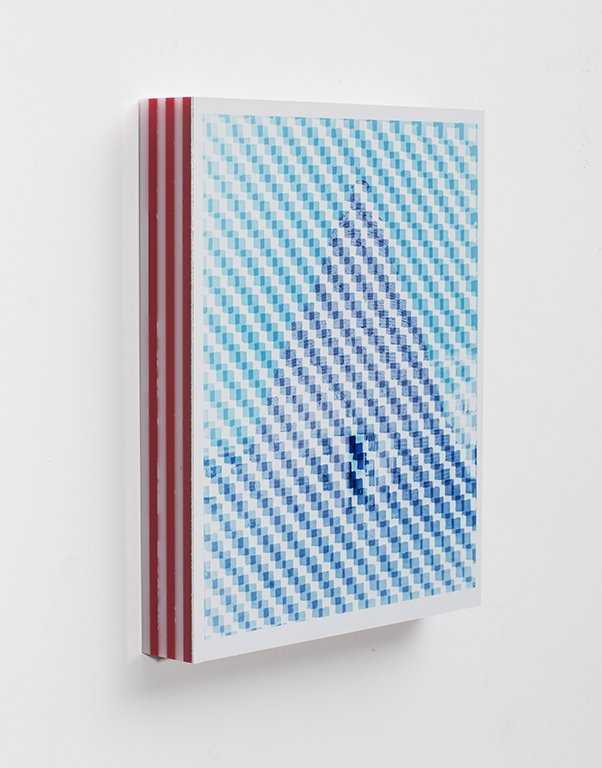

Lateral view

Infinite Rewrite XXV, 2016 Analogue photogram on chromogenic paper, aluminum mount on stacked acrylic base 10.43 x 8.38 x 1.41 in. / 26.5 x 21.3 x 3.6 cm

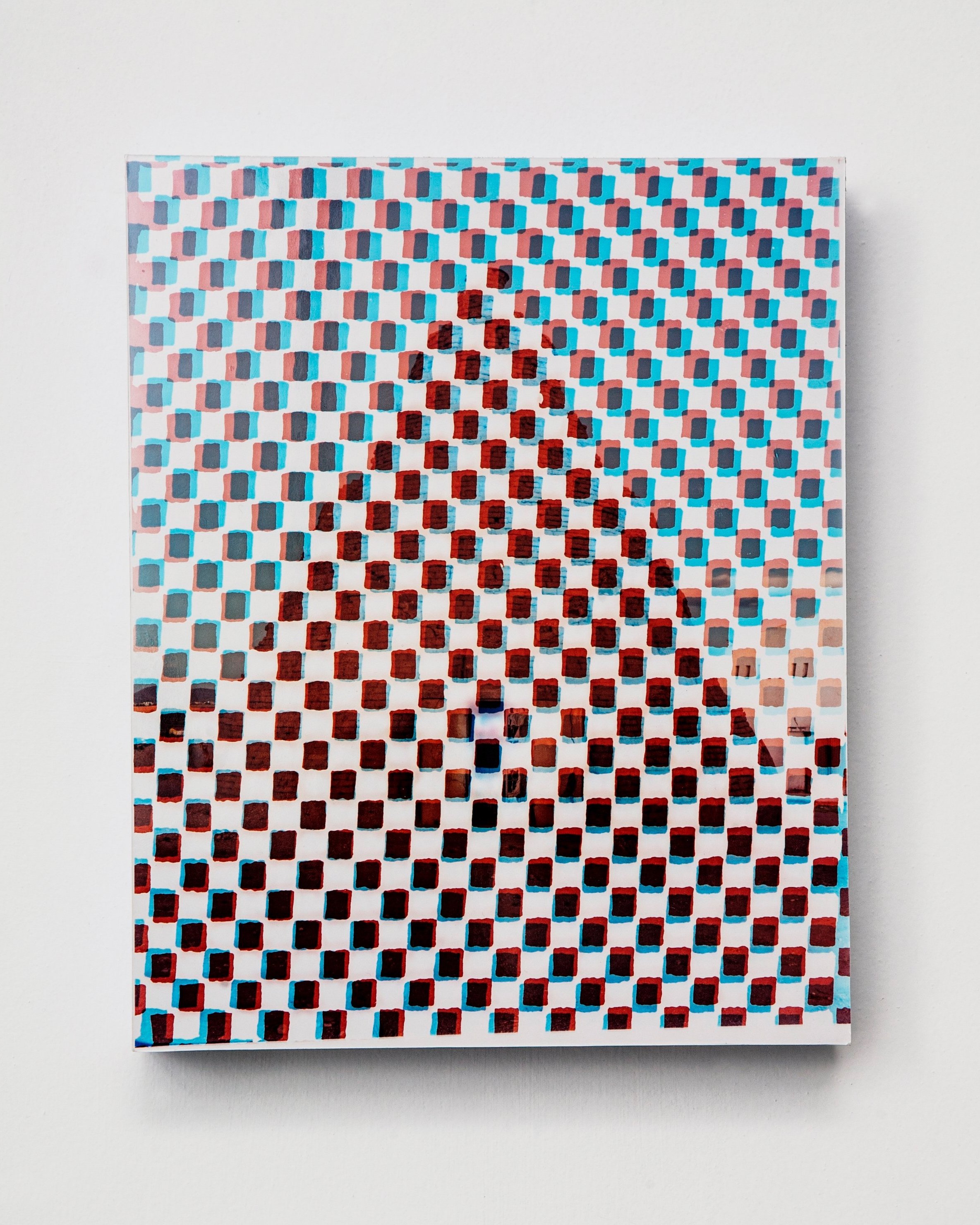

Infinite Rewrite XXXI, 2016 Analogue photogram on chromogenic paper, aluminum mount on stacked acrylic base 10.43 x 8.38 x 1.41 in. / 26.5 x 21.3 x 3.6 cm

Lateral view

Infinite Rewrite VI, 2016 Analogue photogram on chromogenic paper, aluminum mount on stacked acrylic base 10.43 x 8.38 x 1.41 in. / 26.5 x 21.3 x 3.6 cm

Lateral view

Infinite Rewrite XXVIII, 2016 Analogue photogram on chromogenic paper, aluminum mount on stacked acrylic base 10.43 x 8.38 x 1.41 in. / 26.5 x 21.3 x 3.6 cm

Lateral view

Infinite Rewrite XLII, 2016 Analogue photogram on chromogenic paper, aluminum mount on stacked acrylic base 10.43 x 8.38 x 1.41 in. / 26.5 x 21.3 x 3.6 cm

Lateral view

Lateral view

Lateral view

Lateral view

Infinite Rewrite XX, 2016 Analogue photogram on chromogenic paper, aluminum mount on stacked acrylic base 10.43 x 8.38 x 1.41 in. / 26.5 x 21.3 x 3.6 cm

Infinite Rewrite XXXVIII, 2016 Analogue photogram on chromogenic paper, aluminum mount on stacked acrylic base 10.43 x 8.38 x 1.41 in. / 26.5 x 21.3 x 3.6 cm

Lateral view

Infinite Rewrite XXIX, 2016 Analogue photogram on chromogenic paper, aluminum mount on stacked acrylic base 10.43 x 8.38 x 1.41 in. / 26.5 x 21.3 x 3.6 cm

Infinite Rewrite XVIII, 2016 Analogue photogram on chromogenic paper, aluminum mount on stacked acrylic base 10.43 x 8.38 x 1.41 in. / 26.5 x 21.3 x 3.6 cm

Installation view. Nadie Sabe, Nadie Supo. Parque Galería, Mexico City.

NOBODY KNOWS, NOBODY KNEW

Nadie Sabe, Nadie Supo. Parque Galeria. Mexico City, MX.

NADIE SABE, NADIE SUPO, Livia Corona Benjamin’s first one-person exhibition at Parque Galería, is composed of two parts—a series of twenty-one letter-sized photograms, and a single-channel video. While these two parts are formally and visually disparate, each is generated from Corona Benjamin’s long-term project exploring the conical grain silos in rural México known as graneros del pueblo (“granaries for the people”). The twenty-one photograms are part of Corona Benjamin’s ongoing series entitled Infinite Rewrite. Each image features a triangular silhouette composed of granulated particles, which are methodically overlapped and misaligned to create the illusion that the shape is continually crumbling and reassembling itself from picture to picture. These pixel-like marks form an apparently endless variety of optical patterns, like mosaic waves of bricks flowing in irregular streams and eddies. The result is at once contained and euphoric. Individually, each image momentarily establishes its own precarious equilibrium, only to be quickly replaced by the next attempt at pictorial alignment—and then the next, and the next—building to a vigorous jumble of illusion and separation. Though one might assume at first glance that the photographs are digitally generated, each image is actually handmade by the artist, using a single black-and-white negative as a template, working in an analog darkroom. Although Corona Benjamin has made hundreds of photographs of the grain silos throughout the Mexican Republic, her repeated manipulation of a single negative for Infinite Rewrite is a different kind of experiment with variety and difference—a nod, in this case, to the master design for conical grain silos commissioned from Mexican modernist architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez in the early 1960s, and to the many variations of this single design constructed by local farmers in over 1,100 agrarian communities located throughout Mexico. In contrast to the process-driven abstract vocabulary of Infinite Rewrite, Corona Benjamin’s documentary video, titled Nadie Sabe, Nadie Supo / Graneros del Pueblo, investigates the public policy behind these iconic grain silos, as well as the complications so often produced by such government initiatives. The graneros were originally funded by the now-defunct Comisión Nacional de Suplementos Populares (CONASUPO) as a government-sponsored initiative to support farming. In 1970, eight years into CONASUPO’s efforts, over 4,000 graneros had been built, but haste and improvisation compromised the planning and construction, and by 1971 only fifteen percent of the silos were actually functional. Widespread corruption and financial opacity eventually led to CONASUPO’s collapse in 1999. It also, however, bequeathed to the nation an ironic rhyme: Nadie sabe, nadie supo, que fue de la CONASUPO—“nobody knows, nobody knew, what became of CONASUPO”—not to mention what became of the once thriving Mexican rural communities, hosts of what totaled more than 4,000 abandoned silos. At one point, the main narrator in Corona Benjamin’s video asks, “If even those with a college education struggle with job placement, what hope is there for farmers?” He goes on to cite the consequences of the government’s failure to defend the rural way of life, including unprecedented waves of male migration from rural México to the United States, and the displacement of whole families and communities. Both the photogram series and the video deal implicitly with issues of craft and its role in larger social and economic contexts. With Infinite Rewrite, Corona Benjamin deliberately lingers in the moment where an artisan or craftsperson is obliged to retrain the hand to behave like a machine driven by software—a process that reflects the ongoing obliteration of trades and professions by an ever-expanding automation of knowledge work. Using the graneros as a model, she considers the potential for a collective search for renewed purpose, as human experience is confronted with industrialization and the anonymization of process, which parallels the effects of NAFTA and “big agriculture” on Mexican farming. At the same time, Corona Benjamin’s photograms play introspectively with the role of photography in a time of digital repetition and automation, when even newspaper photographers are being replaced with content funnels. Even as she creates images that exaggerate the role of the pixel, she implicitly traces its origins to the ancient art of pre-Hispanic stone mosaic while further anticipating a future when her own manually made pixels will be posted online to swim in the colorful sea of binary code. Perhaps the Web’s inevitable ability to de-aestheticize all imagery, including Corona Benjamin’s hand made rendition of digital pixelation, suggests a kind of parallel to the deconstruction of a magnanimously intended architectural type that, in its own way, came inadvertently to symbolize a particular era of government.