INFINITE REWRITE

Nadie Sabe Nadie Supo IV, 2015 photogram and analog photograph printed on chromogenic paper 25 x 21 x 1.5 in. / 65 x 55 x 3.81 cm. unique piece

Infinite Remax I, 2015. oil paint on canvas 50.4 x 39.4 x 0.98 in. / 128 x 100 x 2.5 cm. unique piece

Nadie Sabe Nadie Supo V, 2015 collage of photograms, archival pigment prints, silver gelatin prints and jade stone 25 x 21 x 1.5 in. / 65 x 55 x 3.81 cm. unique piece

Dream Acts II, 2015 archival pigment print on cotton rag 43 x 35 x 1.7 in. / 109 x 89 x 4.5 cm. unique piece

Mazatlpilli, 2018 pigment inkjet print with turquoise, jade, coral, onyx, obsidian, tiger’s eye and animal bone 39 x 31 in. / 99 x 78.74 cm unique piece

Infinite Rewrite installation view at Parque Galeria. Mexico City, Mexico. 2015

Infinite Rewrite XVI.II, 2015 archival pigment print on cotton rag 30 x 25 x 1.7 in./ 76 x 64 x 4.5 cm unique piece

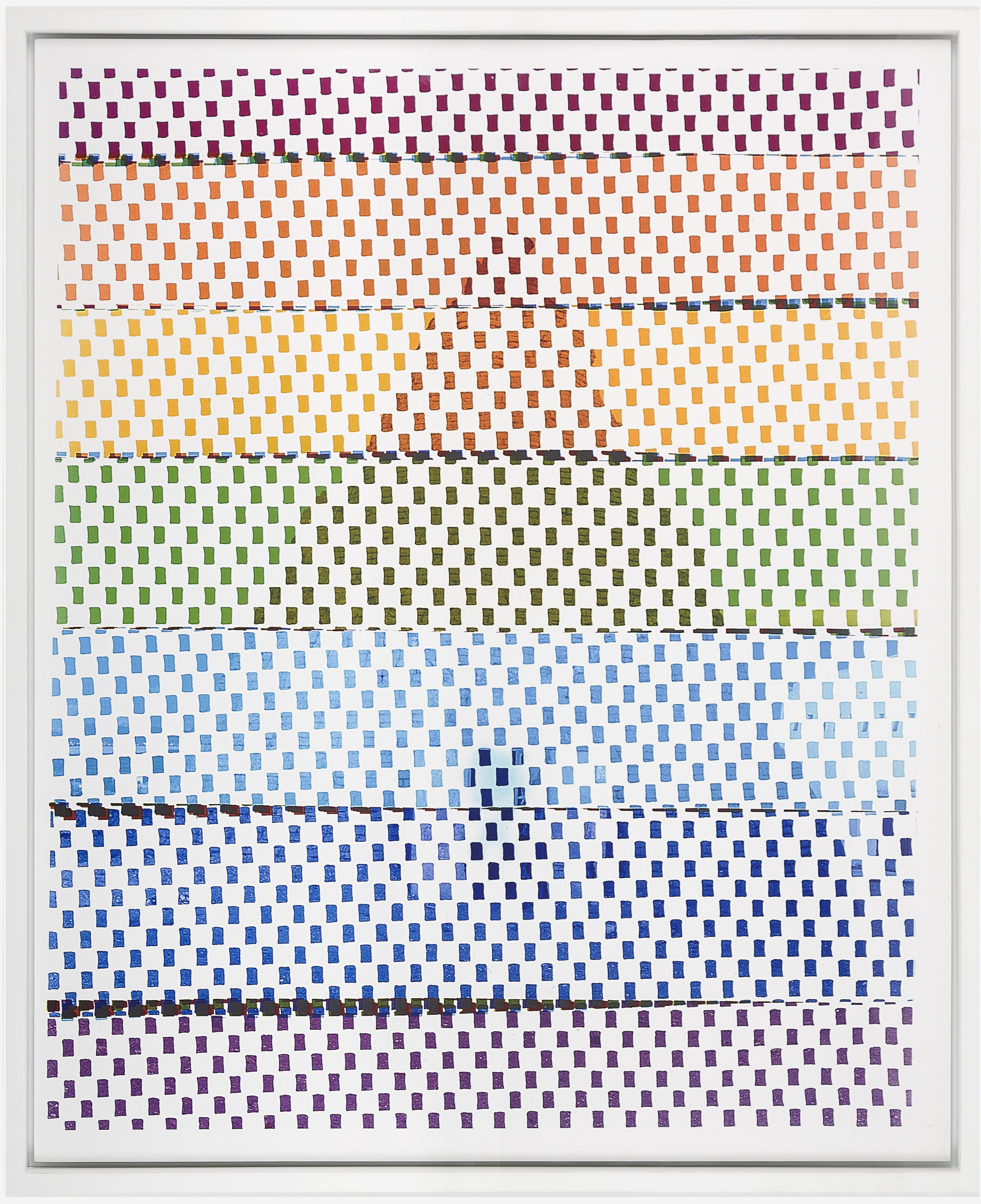

Infinite Rewrite IX.II, 2015 archival pigment print on cotton rag 51 x 43 x 1.7 in. / 130 x 110 x 4.5 cm. unique piece

Infinite Rewrite XVI.II, 2015 archival pigment print on cotton rag 30 x 25 x 1.7 in./ 76 x 64 x 4.5 cm unique piece

Infinite Rewrite installation view at Parque Galeria. Mexico City, Mexico. 2015

INFINITE REWRITE

2015. Inaugural Show. Parque Galería. Mexico City, Mexico

Infinite Rewrite is a series of formally diverse pictures that grew out of my own extensive photo-documentary project about the thousands of conical grain silos found in rural Mexico. However, instead of portraying these remarkable structures with classic photographic prints, Infinite Rewrite attempts to embody their complex history through an improvisatory vocabulary of appropriation and adaptive reuse. Known as Graneros del Pueblo (“grain silos for the people”), the silos were constructed as part of a national initiative to support independent farming communities, under the administration of the Compañía Nacional de Subsistencias Populares (National Company of Popular Subsistence), or CONASUPO. Between 1962 and 1991, more than 4,000 graneros were built in rural and remote regions throughout Mexico for the storage of grains and legumes. The broad distribution of graneros was intended to guarantee fair crop prices for Mexican farmers, while also subsidizing retail prices for national consumers and increasing the price of exports to the international market. CONASUPO had commissioned architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez to design an architectural template that could be replicated by individual farmers within their assigned ejido or communal agricultural land. But Ramírez Vázquez’s conical design is itself an echo of the traditional grain storage barns built on Zacatecan haciendas during Mexico’s colonial era. Although each granero structure is essentially derived from a single design, its final appearance depended on an infinite variety of interpretations and adaptations, which were determined as much by local customs and available materials as by the aptitude of individual ejidal laborers. In effect, the graneros were subjected to a process of potentially endless rewriting, with as many possible variations, even as they continued to retain the same basic structural form. By 1970, just eight years after CONASUPO was founded, a total of 3,558 graneros had been built in 1,109 agrarian communities, representing twenty-one of Mexico’s thirty-one states. However, given the rapid pace of planning and the often improvised methods of construction, in 1971 only fifteen percent of the silos were functional. When CONASUPO was finally closed in 1999, due to corruption and financial opacity, it inadvertently bequeathed to the nation a particular couplet: Nadie sabe, nadie supo, que fue de la CONASUPO (“Nobody knows, nobody knew, what became of CONASUPO”). Not to mention what became of its 4,000 abandoned silos. In fact, many of the graneros remain exactly the same way they were built, rising from the landscape like the silent architectural patrimony of a now archaic-seeming socialism that only a few decades ago had promised so much. Like the sight of pre-Hispanic pyramids in Mexico’s forests invite one to image a pre-Columbian way of life, the “Graneros del pueblo” invite one to imagine a pre-NAFTA Mexican republic in which independent farming was protected and sustained. While thousands of graneros remain empty to this day, many others have been re-appropriated by their communities and diversely repurposed in ways that include schools, evangelical churches, private residences, rural medical clinics, plumbing warehouses, love motels, pig sties, dovecotes, squirrel nests, crack houses, public toilets, and metal smelters. This inventive adaptation of the graneros was key to repurposing the photographic archive I had been making since 1999 (when I first came upon them while traveling across agrarian communities with the Enanitos Toreros on their touring shows). Another visual point of departure for me was Francisco Goitia’s two paintings from the 1940s, exploring the optical effects of color and natural light on the late-nineteenth-century similarly shaped conical silos, which were built at the Hacienda de Santa Monica, in Zacatecas. If the graneros del pueblo were built with brick, mortar, stone, adobe, wood or concrete, the building blocks of my images are film, light, color filters, photographic papers, chemicals, inkjets, collage, and of course, pixels on a screen—an infinitely rewritable sequence of zeros and ones. Infinite Rewrite is a means of appropriating this history of construction, collapse and reuse as a pictorial and conceptual method that is capable of optically breaking down and readapting my own documentation.